We’ve been here before, and we know what comes next: White supremacy has always been used to usher in massive economic inequality

We’re a little over a year into the second Trump presidency. That second term began with the establishment of “The Department of Governmental Efficiency” (DOGE), a sustained campaign to discredit and undermine the usefulness and work of federal institutions and employees, and the issuance of multiple executive orders rescinding prior guidance on equity, including those related to federal affirmative action. The dismantling of entire federal agencies, alongside massive cuts in their capacity to make progress toward equity goals, swiftly followed (USAID, HHS, and the Department of Education are some of the most impacted agencies). During the summer of 2025, Republicans passed a spending bill that massively increased the size and scope of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), while giving huge tax breaks to the wealthiest Americans and making drastic budget cuts to social assistance programs.

Throughout this second term we’ve also seen a steady increase in white supremacist rhetoric and images coming from government officials: Agency-run social media accounts make appeals to the homeland, remigration, and other white nationalist dog-whistle phrases, while the president himself continues to demonize nonwhite immigrants and cities with large minority populations, and to mischaracterize the Civil Rights Movement as harmful to white people.

These actions and rhetoric are not simply poor governance; they follow a historical script that white supremacists in the United States have used for centuries to undermine progress toward equity. Each time, that script sets the stage for policy changes that lead to a massive increase in economic inequality. Here’s the pattern:

- Establish distrust in progressive goals by raising the specter of racial minorities corrupting and taking advantage of a government that has “overstepped its authority.”

- Severely curtail government functions by dismantling existing programs directed toward progressive policy goals (e.g., equity, poverty prevention) and allowing others to expire, halting forward progress.

- Institute methods of targeting and controlling nonwhite populations, increasing economic insecurity, stoking fear, and lowering their political and economic power relative to white peers.

Consider what took place in the half-century following the Civil War, as the United States tried and failed to rebuild itself into a multiracial democracy for the first time:

- Establish distrust: Disaffected ex-Confederates led campaigns of misinformation alleging that newly elected Black government officials were corrupt and undeserving, that the government itself had overreached by sending federal troops to ensure that Southern states followed the law with respect to racial inclusion, and that allowing Black men the vote presented an existential threat to white men, women, and children. In the West, white supremacists spread similar misinformation about Chinese immigrant workers.

- Halt forward progress: Federal troops were removed from Southern states, exposing Black families to horrific acts of economic, social, and spiritual violence from white vigilantes; institutions like the Freedmen’s Bureau and Freedman’s Bank were dismantled and allowed to collapse, curtailing progress toward integrating Black families into the U.S economy with dignity.

- Target and control nonwhite populations: White supremacists in government passed legislation limiting the economic, social, and political rights available to nonwhite Americans, most notably Jim Crow laws and the Chinese Exclusion Act. These policies led to significant economic precarity for nonwhite workers, allowing exploitative systems like sharecropping to thrive and ensuring railroad workers and miners had little recourse to protest poor working conditions.

This reassertion of white supremacy saw the government take a big step back from progressive goals and ushered in one of the most unequal and unstable ages of U.S. economic history: The Gilded Age.

For a more recent example, consider the 40-year-long backlash to racial progress made in the mid-20th century through the efforts of the Civil Rights Movement (beginning with the first Reagan administration in 1980):

- Establish distrust: Disaffected conservatives employed an intellectual strategy (neoliberalism) designed to cast government as the source of America’s economic woes, rather than a tool that could be used to alleviate them. Neoliberalism recast the social safety net that had been designed to keep poor and working-class families, children, and the elderly out of poverty as a hammock in which lazy, undeserving Black people (especially single Black mothers) could comfortably take advantage of taxpayer dollars.

- Halt forward progress: Citing the myth of an undeserving, perpetually dependent “underclass,” Republican and Democratic administrations alike took action. They made major cuts to programs designed to alleviate economic hardship, halting progress toward closing racial gaps in poverty because Black families are more likely to be impoverished. The federal government added strict work and income requirements to social programs like food stamps (SNAP) and Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC, eventually replaced by the much less adequate TANF) that decreased their efficacy. The government stripped institutions devoted to enforcing and advancing civil rights like the EEOC and the Commission on Civil Rights of funds and reduced their scope.

- Target and control nonwhite populations: Beginning in the 1970s the United States embarked on an unprecedented expansion of policing and the carceral state; the development of this mass incarceration led to an explosion of arrests, convictions, and crucially, imprisonment. Nonwhite men were and still are overwhelmingly the targets of this system, with Black incarceration rates six times higher than those of white people. Incarceration serves as a tool of economic stratification that renders Black and brown workers noncompetitive with white workers and severely limits the capacity of Black and brown families to accumulate wealth, alongside a host of other imposed disadvantages.

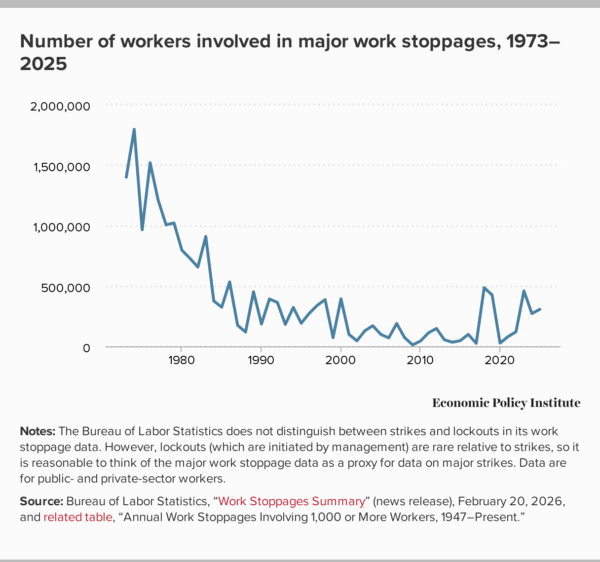

The wealthiest owners of capital used white supremacy to shape policy decisions such that they could capture a greater share of economic power and resources, influencing government to withdraw resources previously used to support and protect workers and families of all shades. This also set the stage for weakening labor standards, chipping away at workers’ rights to organize, allowing globalization to displace blue-collar workers, and influencing the Fed’s tolerance of excessive unemployment.

Further, as more of our national spending shifted toward law enforcement rather than social welfare, racial targeting increased, poverty was criminalized, and so too did a greater share of income go to the top percentile earners. Significant progress toward racial economic equity—little that there was—has all but ceased since the 1980s.

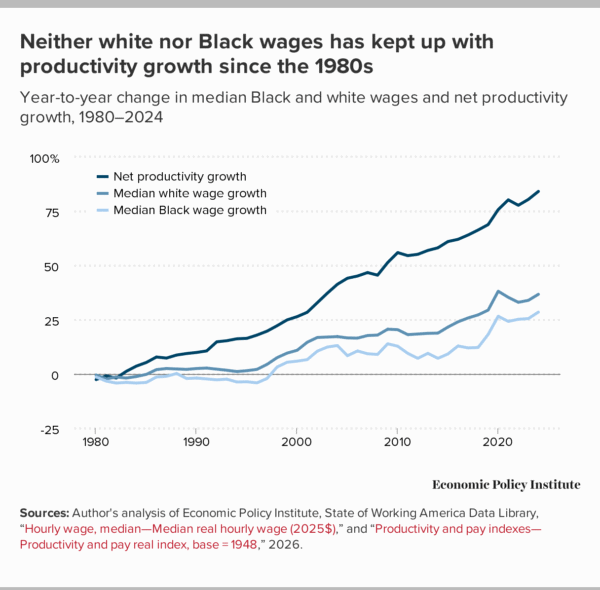

Figure A shows the raw deal that both Black and white workers have been given since the 1980s. While the workforce became around 84% more productive between 1979 and 2024, workers’ wages grew much more slowly. Typical white workers’ wages only grew 37% over the same period, while Black workers’ wages grew even more slowly at 28.5%.

Figure A

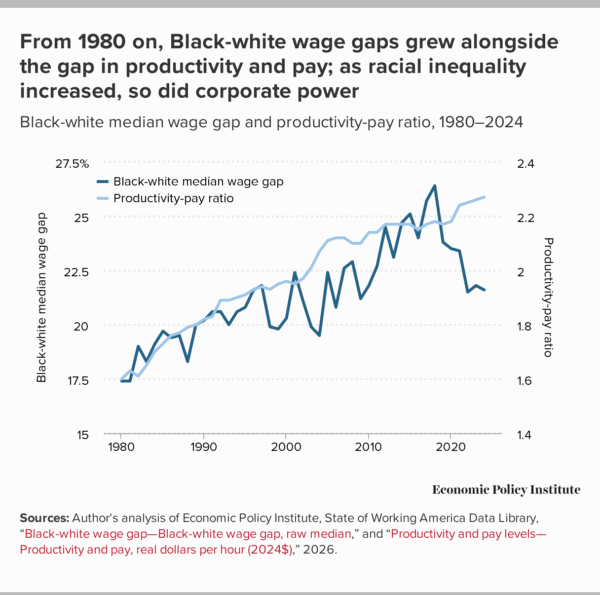

Figure B shows how racial wage inequality increased along with rising corporate power. The darker line here represents the extent to which workers’ productivity increased faster than their pay (the ratio of net productivity—or output per hour—to total compensation per hour); in other words, the extent to which employers were able to capture a greater share of economic output than workers. As the wage gap between typical Black and white workers increased (from 16.6% in 1979 to 21.6% in 2024, a growth rate of 30%), so too did the gap between productivity and pay (from 160% in 1979 to 227% in 2024, a growth rate of 42%). In this view, white supremacy works as a wedge by which the working class is separated, weakening worker power and allowing the productivity-pay gap to increase.

It took the labor market shock and reset of a global pandemic, and the rapid, expansionary policy response toward it, to finally break the decades-long trend of increasing Black-white wage inequality; the resulting tight labor market saw faster wage growth between 2019–2024 for low-wage workers (who are disproportionately Black and brown) than for any period since 1979, and a drop in the Black-white wage gap from its peak in 2018 at 26.4% to 21.6% in 2024. This relatively rapid reduction in Black-white income inequality provides important context for our current wave of white supremacist backlash.

Figure B

White supremacy has always been employed in the United States as a political economic strategy for maintaining social hierarchy. That hierarchy is consistent both with the assertion of white privilege and with corporate interests. The value in maintaining white supremacy for the interests of wealthy elites is that it complicates class solidarity across racial lines, while also pre-establishing a population of workers who exist along a spectrum of exploitation.

The most exploitable of these workers (e.g. Black, brown, women, and/or poor workers) have little to no recourse for protection nor serious prospects of changing their class position without explicit outside intervention, even across generations. Workers with more proximity to power (e.g. white, male, and/or high-income workers) have access to real social and material benefits that come from their relative position, and so are incentivized to maintain the status quo. Even still, these workers face exploitation and economic precarity as the truly wealthy continue to build capital, and their share of the nation’s income and wealth continues to rise.

The Trump administration’s motivations are clear when viewed through the lens of white supremacist political economy. This framing puts Project 2025 into its proper historical context as a recycled agenda designed to reassert the social and economic privileges of white Americans relative to their Black and brown neighbors, pacifying potential white opposition toward policies that will most enrich the few at their absolute expense. If this historical script is allowed to run its course—that is, if the administration is successful at establishing distrust in the efficacy of government, halting what forward progress we’ve made toward equity and progressive goals, and targeting and controlling nonwhite populations—the final act will be another massive increase in economic inequality and instability, a period in which most American families will suffer.

There is a path forward, however. Progress toward racial equity has always threatened consolidated class power, particularly in the United States. A working-class coalition across racial lines has historically been a dangerous prospect for those invested in maintaining inequality because it creates the possibility of a serious inversion of power, a realization that solidarity could genuinely result in a more equitable distribution of the costs and benefits of production. Building a genuine multiracial democracy in which people from all groups can expect to be treated with dignity and have access to the same economic security and opportunity is a real path toward breaking down inequality run rampant.

Here’s the bottom line. When we see:

- A concerted effort to discredit and defund the important work done by Black and brown women government employees to move us toward equity (Establish distrust)

- The tearing down of historic laws and institutions devoted to providing equal access to opportunity and security to all Americans (Halt forward progress)

- The terrorizing of nonwhite workers and their families in places of work and worship alike (Target and control nonwhite populations)

We must recognize these efforts as intentional ones that lead us all—white workers and their families included—down a path to greater economic inequality, instability, and injustice.

Recent comments