There were two somewhat important economic reports for October released last week, coincidentally both rescheduled for release at 8:30 AM on Wednesday, retail sales from the commerce department and the consumer price index from the bureau of labor statistics (BLS).. Together they're often used by economists to generate a metric that goes by 'real retail sales', which is supposed to be something analogous to the real personal consumption expenditures metric of GDP, and which is said to be an indicator used by the NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee to determine turning points in the economy, ie, the beginning and end points of official recessions. Even the Fed generates a graph for real retail sales from these two reports, constructed by a simple deflation the monthly retail sales results with the change in the consumer price index of the same month. The last time we covered these two reports together we suggested that this metric was an inexact and crude measurement that was prone to leading to incorrect conclusions about the direction of the economy, especially in the way it's viewed by the Fed, NBER (National Bureau of Economic Research) and most economists. Today we're going to show why it's wrong, and moreover, point to the correct way real retail sales should be calculated. But before we do that, we'll take a look at the two reports in question.

October Retail Sales Increase 0.4% on Unexpected 1.4% Jump in Vehicle Sales

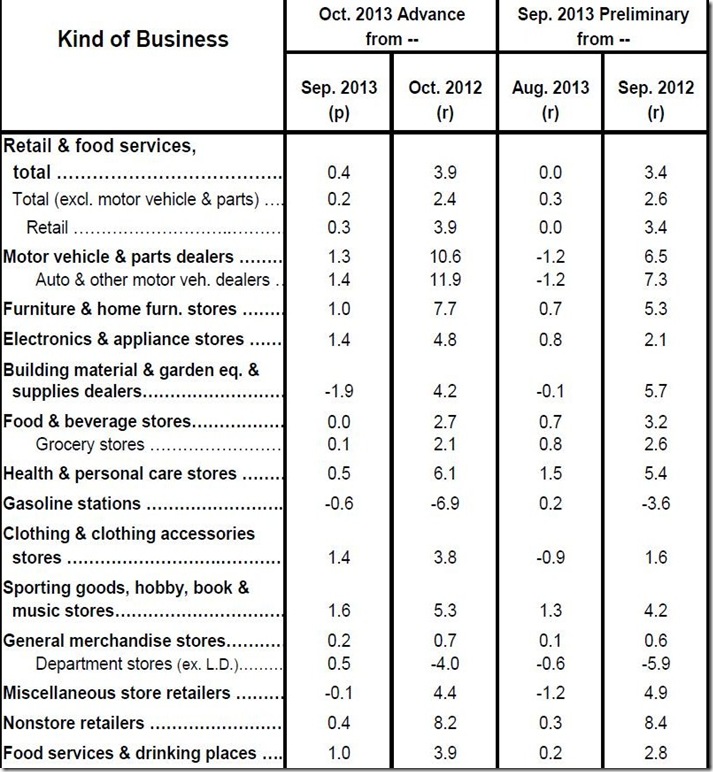

According to the Advance October Report on Retail and Food Service Sales (pdf) from the Census Bureau, seasonally adjusted retail and food services sales were at $428.1 billion in October, an increase of 0.4 percent (±0.5%)* from September and 3.9 percent (±0.7%) above October 2012. Unadjusted retail sales, extrapolated from a small sampling, were reported at $421,946 million, an increase over the revised September sales of $402,927. That asterisk points us to a footnote that tells us Census doesn't not yet have sufficient statistical evidence to determine whether seasonally adjusted sales actually rose in October of not, but that they're 90% certain the September to October change was between a decrease of 0.1% and an increase of 0.9%. With that caveat, we'll look at these widely followed advance estimates as reported...

October sales were better than expected; the consensus of analysts had forecast no change in total sales, due to an apparent decrease in October auto sales based on reports from manufacturers. However, the small sampling of auto and other vehicle dealers surveyed for this report indicated their actual sales for the month had increased 1.4% over September, adding to October's sales increase rather than subtracting from it. Including parts dealers, October's seasonally adjusted sales in the vehicle sector were at $81,871, a 1.3% increase over September. That percentage change is shown in the first column in the table below from the report, where we can also see in the second column that the percentage change from October 2012 for auto and other vehicle dealers was 11.9%, with a 10.6% year over year sales increase for the whole automotive category. Also note that total retail sales excluding motor vehicle & parts dealers were up 0.2% for the month, also beating expectations...

It's also clear from looking at that first column above that most kinds of business, except for building and garden supplies and gas stations, saw seasonally adjusted sales rise, led by a 1.6% month over month increase in the sporting goods, hobby, book & music store group, who saw seasonally adjusted sales rise to $7,714 million for the month. Clothing stores rebounded to show a 1.4% month over month increase while selling $37,847 million of clothing and shoes, and electronics and appliance retailers also saw October sales rise by 1.4% to $8,699 million, while furniture stores logged a one month sales increase of 1.0% to $8,687 million, as did restaurants and bars, whose October sales were at a seasonally adjusted $46,317 million. Also showing month over month sales gains were drug stores (health and personal care) at 0.5%, where $24,327 million of products were sold in October, non-store or online retailers, who moved $37,847 million of merchandise, 0.4% more than September, and general merchandise stores, where sales of $55,303 million were up 0.2% for the month. Meanwhile, food and beverage store sales were virtually unchanged, with seasonally adjusted sales rising to $54,693 million in October, from $54,682 million in September, gas station sales fell 0.6% to $45,165 million as gasoline prices fell 2.9%, and sales at building material & garden equipment stores fell 1.9% to $25,793 million. Also note that miscellaneous retailers, where sales fell 0.1%, account for another $10,609 million sales for the month…

Also note the third and fourth columns on the table above, which represent the 2nd estimate of retail sales for September. As originally reported, retail sales were down 0.1% to $425.9 billion in September. That estimate has now been revised to a preliminary figure of $426.369 billion, and that works out to a 0.0% change from the seasonally adjusted sales of $426.355 billion in August. The major revision to September sales was in in motor vehicles and parts sales, which were originally reported at $79,773, down 2.2% from August; that's been revised to show September motor vehicle and parts sales at $80,815 million, down just 1.2% from August.. Other retail sales groups which saw sales revisions of more than 0.2% included clothing stores, which were originally reported to have seen September sales fall 0.5%, which has now been revised to a 0.9% drop; the sporting goods, hobby, book & music store group, originally reported to have seen just a 0.5% change who've now seen their September totals rewritten to indicate a 1.3% sales gain; general merchandise stores, initially reported as up 0.4% which has been revised to just a 0.1% increase; and restaurants and bars, where September sales were reported up 0.9% three weeks ago, which has now been revised to just a 0.2% gain from August. On net, this revision suggests a small upward revision to the durable goods component of PCE in 3rd quarter GDP, partially offset by an even smaller downward revision to non-durable goods.

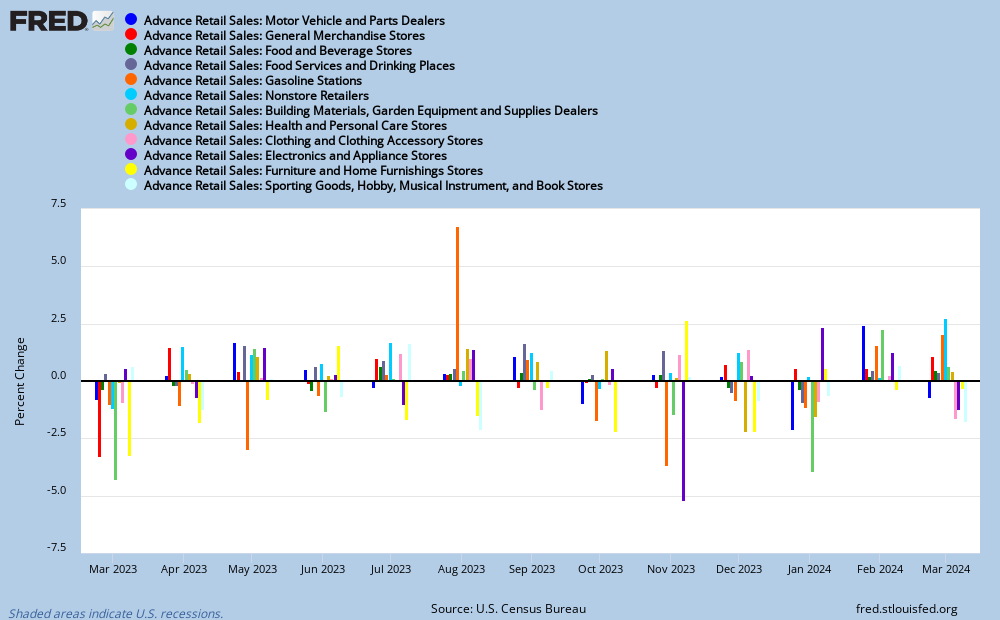

Our FRED bar graph below shows the monthly percentage sales change for each of the 12 major retail sales categories since last October.. The monthly data for each of the past 13 months is represented by a grouping of 12 bars, with each type of retail sales represented by its own color code in each group, wherein an increase in sales appears above the ‘0’ line and a decrease below it. From left to right in each group is a dark blue bar representing the percentage change in motor vehicles and parts sales, a red bar indicating the change at general merchandise stores, followed by the percentage change at food and beverage stores in green, the sales change restaurants and bars in mauve, the change at gas stations in orange, the change non-store or online retailers in sky blue, the change at building and garden supply stores in light green, the percentage change at drug stores in mustard, the change in sales at clothing stores in in pink , the change at electronics and appliance stores in purple, the change at furniture stores in yellow, and the percentage change in sales at stores specializing in sporting goods, books or music in pale blue…(click to enlarge)

Slowest Annual Inflation Since 2009 as October Consumer Prices Fall 0.1% on Lower Gas Prices

Also seeing a delayed release on Wednesday, the Consumer Price Index for October from the Bureau of Labor Statistics was one of the economic reports most profoundly effected by the government shutdown because its input data is normally collected by an army of field agents who visit thousands of retail stores, service establishments, rental units, and doctors' offices, et al each month to track changes in price in the items appearing in the index. To compensate for the loss of 16 days of such data collection, BLS personnel normally devoted to in-office maintenance work were redirected into field data collection and index production, and as a result BLS managed to collect roughly 75 percent of the amount of prices normally used in constructing the CPI, albeit only during the last two weeks of the month, absent prices from the prior days. Understanding that this may make the results less reliable, we'll go with what's reported, since considering the methodology, there wont be any revisions anyhow...

The seasonally adjusted Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) decreased 0.1% in October; entirely due to lower energy prices, as the energy price index fell 1.7% on gasoline prices that were 2.9% lower in October than September. Meanwhile, the food price index rose 0.1%, and the Core CPI, which is the index of all prices less food and energy, also rose 0.1%.. The unadjusted CPI, which is based on prices over 1982 to 1984 equal to 100, fell from 234.149 in September to 233.546 in October, and the unadjusted energy index fell from 248.513 to 238.524, while the food index rose from 237.522 to 237.871 and the Core CPI rose from 234,782 to 235.162. The CPI is now up just 0.96% to 231.317 on a year over year basis, the lowest annual inflation rate since October 2009, while the Core CPI has logged a 1.68% (rounded to 1.7%) annual rate of inflation for all items less food and energy...

Other than 2.9% lower prices for gasoline, items in the energy price index which fell in price in October included fuel oil, which was down 0.6%, the index for propane, kerosene and firewood, which slipped 0.4%, and other motor fuels, which also were 0.4% lower; the energy services index was off 0.2%, as a 1.0% decrease in the price of natural gas was partial offset by a 0.1% increase in the cost of electricity. On a year over year basis, the energy price index has fallen 4.8%, as the 9.5% decrease in energy commodities outweighed the 3.3% increase in energy services.

Both of the major components of the food price index, food at home and food away from home, were up 0.1% in October, as was the overall food index. Among categories of food at home, prices for cereals and baked goods fell 0.4% for the month, as bread prices fell 3.0%, flour prices fell 0.9%, and the rice pasta and cornmeal index rose 2.2%, while dairy products were 0.2% lower as a 1.3% drop in cheese prices and a 1.4% drop in ice cream prices offset an 0.3% increase in milk prices. Meanwhile, prices for meats, poultry, fish, and eggs rose 0.6% on a 1.0% increase in pork prices, 1.5% higher prices for fish and other seafood, and 1.8% higher egg prices, while fruit and vegetable prices were 0.2% higher as lettuce prices rose 4.0%, citrus fruits rose 1.9%, fresh fruits other than apples, bananas and citrus rose 3.2%, while prices for processed fruits and vegetables fell 1.2%. In the beverage group, which saw prices rise 0.4% in October, roast coffee prices increased 0.7% and carbonated drinks fell 0.1%, while the catch all category of other food at home saw a 0.2% price decline, as sugars and sweets rose 0.4%, snacks rose 0.5%, while both butter and margarine and spices and seasoning prices fell 1.1%. In the food away from home grouping, fast food prices rose 0.2%, full service restaurant prices were unchanged, and food purchased at work and school cost on average 0.8% more than it did in September..

Among core prices that increased in October, the cost of shelter rose 0.1%, as rents for one's primary residence rose 0.2%, homeowners equivalent rent rose 0.2% while room prices at hotels and motels fell 4.0%; the cost of apparel fell 0.5%, as men's and boys clothing rose 0.8% as prices for pants and shorts were up 10.2%, women's and girls' apparel fell by 0.8% on 2.2% lower prices for girls clothing, while the prices for footwear fell 0.6%. The overall transportation index, which includes fuel costs, showed a 0.7% decline, but prices for transportation commodities less fuel were unchanged, as prices for new cars and trucks fell 0.2% while prices for used cars and trucks rose 0.3% and parts and accessory prices fell 0.1%. Meanwhile, prices for transportation services rose 0.7% in October as public transportation costs rose 2.2% on a 3.6% spike in airline fares. The medical care index showed no change for the month as medical commodities were up 0.3% in price on a 0.6% increase in nonprescription drugs prices while costs for medical care services were off 0.1% on 0.2% lower hospital and related services..In addition, the recreation index rose 0.1% as prices for recreation commodities were unchanged overall as prices for video & audio equipment fell 0.4%, offsetting increases of 0.4% in prices for sporting goods and pets and pet supplies, while recreation services prices increased 0.2% on a 0.4% increase in cable and satellite service and a 05% increase in veterinary and other pet services. The last major price index, for education and communication, showed a 0.2% increase in October as education costs were up 0.4% and communication prices were unchanged; within education and communication commodities, which were down 0.4%, textbook prices were up 1.0% and personal computers fell 1.3% in prices, while education and communication services rose 0.3% for the month as college tuitions were up 0.4% and telephone services rose 0.2%.

Our FRED graph below shows the relative price change in each of these major components of the CPI-U since January 2000, with all the indexes reset to 100 as of that date to make for an apples to apples comparison, as two of the composites were restructured in 1997 and the others are based on 1982-4 price. iin blue, we have the track of the change in the price index for food and beverages, which tracks pretty close to the track of the CPI-U, which is shown in black. In red, we have the change in the price index for housing, which includes rent and equivalents, utilities, repairs and other homeowners costs like insurance and which at 41% of the CPI also tracks close to the CPI. In violet, we have the price index for apparel, which has been the only index to show a net price decline over the decade. The transportation index, in brown, shows the impact of volatile gas prices on the cost of transportation, while the price index for medical care in orange has obviously risen the most over the entire period. In addition, education and communication prices are tracked in dark green, and the track of the recreation price index is shown in light green..

We Find Real Retail Sales Rose .75% in October

Now, as we mentioned in opening, an economic metric called "real retail sales" is commonly constructed by using the CPI to adjust retail sales for the same month. The reasoning behind this is that we'd want to know how many units of product were sold, not just the dollar value, and if prices were rising (or falling), the retail sales figures, which do not adjust for price changes, we'd get a skewed result. For instance, if the retail sales report told us the dollar sales of apples were up 5% month over month, the actual change in the number of apples sold couldn't be determined unless we knew if prices for apples changed or not, and by how much. And the reason we would want to know real retail sales early is because real personal consumption expenditures (adjusted for inflation) constitute 70% of GDP, and although that is mostly spending for services, spending for durable goods like cars and appliances, and non-durable goods, like food, clothing and gasoline, still make up a third of expenditures, or over 23% of GDP. In the common method of computing real retail sales for October, the increase in dollar value retail sales of 0.4% is adjusted for prices that were 0.1% lower, suggesting that real retail sales had increased by 0.5% for the month (or 0.47%, using two decimal places). But as we've seen in reviewing these two reports together, the expenditures they cover don't really match up; in fact, more than 60% of price changes covered by the CPI are for services, not products sold at retail at all. So, if we use the CPI to adjust retail sales for inflation, there's a good chance there will be months where the price change in many of the items sold at retail would go in a different direction than the majority of the CPI components. To put it another way, by adjusting retail sales with the CPI, we'd often end up adjusting sales of cars, clothing, and appliances with the price changes of doctor's visits, apartment rents, airfares, and tuition increases. The only correct way to adjust retail sales with the CPI would be to itemize retail sales and adjust it with the corresponding CPI component price change. We'll run through an example of how that could be done here using our October data, but as you'll see it's a very tedious process better left to an automated program..

The largest component of retail sales is sales at motor vehicle & parts dealers, which at a seasonally adjusted $81,871 million in October accounted for 19.1% of total retail sales; of that, $75,035 million was from vehicle sales, and the rest was sales at parts and tire stores. And as we saw, sales at car dealers increased 1.4% in October. We have two components of the CPI which are suitable to adjust the vehicle sales for inflation; prices for new cars and trucks, which were down 0.2% and prices for used cars and trucks, which were up 0.3%. The weighting of new vehicles in the CPI was 3.133, and the weighting of used vehicles was 1.889, which means that new vehicles were five-eighths of vehicle sales, and used vehicles accounted for three-eighths; so we want to adjust 5/8ths of the 1.4% increase up by 0.2%, and 3/8ths of it down by 0.3%, which quite coincidentally gives us a real vehicle sales increase of just over 1.4%, not much change. Also buried in that aggregate motor vehicle data are sales of parts and tires, which were up 0.48% in October, while the corresponding prices for motor vehicle parts and equipment were down 0.1%, resulting in a real sales increase of .58%. So in a quick and dirty calculation, we have real retail sales for the motor vehicle & parts dealers component up 1.346% for October. Moving on, another large component of retail sales is sales at food and beverage stores, which accounted for 12.8% of retail sales and saw dollar value sales virtually unchanged in October. Applying the 0.1% increase in the 'food at home' index of the CPI to those sales, we thus find that real retail sales at food and beverage stores fell 0.1% in October. There were also $46,317 million in sales at restaurants and bars in October, or 10.8% of retail sales; those sales increased 1.0% month over month, and we'd deflate them with "food away from home" from the CPI, which indicated a 0.1% MoM price increase; thus real retail sales at bars and restaurants increased 0.9% in October...$45,165 million in sales at gasoline stations were down 0.6% according to the retail sales report, where they accounted for 10.6% of sales; however, the gasoline component of the CPI tells us that gasoline prices were down 2.9%, so real sales at gasoline stations were up around 2.3%. Sales at furniture stores, at just over 2% of retail sales, were up 1.0%, which was not broken down into types by the retail sales report, whereas there are prices for a dozen separate items that might be found at a furniture store on the detailed CPI list. So to adjust furniture sales for inflation, we'd use the overall 'household furnishings and supplies' component of CPI, which includes several non-furniture items but is still mostly furniture with appropriate weightings; prices for that index were down 0.2%, and thus we'd conclude that real furniture sales were up 1.2% in October. Sales of $55,303 at general merchandise stores, which were up 0.2% and account for 12.9% of retail sales, presents another problem, in that these stores sell a wide range of merchandise for which there's probably over a hundred CPI entries. We'd suggest adjusting those sales with the price change for consumer "commodities less food and energy commodities", which includes all retail items except food and energy, and which was down 0.1% for October, and thus results in a real sale increase of 0.3% at general merchandise stores. The $8,699 million of sales at electronic and appliance stores were not broken down in October, but in prior months appliances, TV & camera stores accounted for about 3/4ths of those sales and computers and software stores were the rest. Together they accounted for just over 2.0% of retail sales and increased 1.4% in nominal terms. In the CPI index, appliances, unchanged in price, are a household item, TVs, down 0.6% and cameras, down 0.1% are entertainment, while personal computers, down 1.3%, are educational; using the CPI weightings of each, we figure a 1.6% real sales increase in TV and appliances sales, and a 2.7% real sales increase in PCs and related equipment, giving us a 1.9% increase in real unit sales for the retail group. Computing the other retail businesses in a similar manner, we find that real sales at clothing stores, which account for over 4.9% of retail sales, were up 1.9% in October; while real sales at drug stores, which account for 5.7% of sales, were up 0.4% based on weighted price indexes of personal care products and drugs. Real sales at sporting goods, hobby, book and music stores, which account for 1.7% of retail, are up 1.6%, same as the actual increase, when adjusted with the unchanged recreational commodity index, and real sales for non-store retailers, which account for 8.8% of retail and adjusted as general merchandise, were up 0.5% in October. We also find that real sales at building and garden supply stores, which at $25,793 million account for 6.0% of retail sales, when adjusted with prices for tools, hardware, outdoor equipment and supplies, were down 2.0% in October and that miscellaneous store retailers, at 2.5% of the total, saw no change in real retail sales..

Now that we've done this exercise of computing the real retail sales percentage change of each business group covered by the retail sales report, we have to add them together to come up with a final figure for real retail sales, so we'll express that math in a detailed longhand expression so we all can see what we're doing. Real retail sales for October = 19.1% * 1.346% + 12.8% * -0.1% + 10.8% * .9% + 10.6% * 2.3% + 2% * 1.2% + 12.9% * .3% + 2.0% * 1.9% + 4.9% * 1.9% + 5.7% * .4% + 1.7% * 1.6% + 8.8% * .5% + 6.0% * -2.0% + 2.5% * 0% = + .75%, assuming we've done the math right. So our calculation of real retail sales is apparently nearly 0.3% higher than the simplistic method of just deflating total sales with the CPI. One obvious reason that would account for much of the difference was the gas station sales component, which would have been carried as down 0.5% when deflated with CPI-U, but is apparently up 2.3% when deflated with gasoline prices. Perhaps some combination of gasoline and tires, batteries and accessories would have been a more appropriate deflator, but we have no data on which to base that percentage. Another reason that this workout produces a higher real retail sale result is more valid; that being that prices for items bought at retail (aka commodities in CPI jargon) have been trending down in price while prices for services have generally been up; that's clear just from reviewing some of what we saw in this month's CPI core data; it makes no sense to deflate car sales (transport commodity) with the 3.6% spike in airfares (transport service). But that's the kind of thing actually being done when the NBER, the Fed and other economists deflate retail sales using the entire CPI.

(crossposted from Marketwatch 666)

Comments

me thinks you are halfway to NIPA

I'd have to go digging around in the handbook of methods, but I believe the price deflator for PCE, where retail sales would be an input, is broken down per category.

You'll have to dig there if you haven't, but it's very common for the Census reports to have just a rough element to them and all sorts of "fun stuff" happens when going over the to BEA for inputs into the national accounts and thus GDP and so on.

Good effort, hey, we live for number crunching on EP!

it's been bothering me for a while...

i've mentioned in comments on economic blogs several times that the CPI was inappropriate as a deflator for retail sales, since higher prices for services were the driver in CPI increases, and the responses, when i've got them, have been that's the was the NBER and Fed do it...when the two reports came out on the same day last week, i figured it was time to try my hand at it, especially since i botched my last attempt...

rjs

did you try calling up the Census?

As long as one is polite and has a clue, one can ask questions via phone to clarify. I have to agree it doesn't make that much sense to to divide by CPI when auto sales are the biggest chunk of retail sales.

i'd call FRED

i havent seen the census use that real retail sales metric; it's most often cited on economic blogs, using the FRED graph: http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/RRSFS

doug short at advisors perspectives does at least one and sometimes more than one post a month on real retail sales, citing the NBER's use of it as an indicator (linked in the first paragraph above); since he's dismissed my challenge to it in the past, i figure i'll write him with a link to this...

rjs

It is a Census series

FRED just takes various data series via ftp and puts it into their database and graphing system, retrieval system. If the data is from the Fed, it is usually identified as such. BTW: Complain to FRED about the new beta. I fear disaster for graphs if you check it out. We need the current system available.

census and BLS

here's the FRED explanation for RRSFS:

This series is constructed as Retail and Food Services Sales (http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/RSAFS) deflated using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (1982-84=100) (http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/CPIAUCSL).

rjs

Right, BLS is CPI, PPI, Census is Retail Sales

But the application of CPI to Retail Sales is published by the Census, so place to start to detail is probably them and you can ask why they don't apply the individual CPI for categories to the subcomponents of retail sales first. In other words, CPI has values for all sorts of services and goods, different inflation figures for eggs, veggies, trucks, regular autos, even diesel fuel. So, one could take the corresponding CPI subseries and apply it to the subcategories of retail sales.

The PCE price deflators I believe break down similarly but I haven't studied the handbook enough. (hey, someone PAY ME to do that!) ;)

confirmation on real retail sales..

last weeks Incomes and Outlays for October had real durable goods PCE up .8% and non-durable PCE up .7...

end of table 7: http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/2013/pdf/pi1013.pdf (Percent change from preceding period in chained (2009) dollars, seasonally adjusted at monthly rates)

my guess at ~.75 wasnt half bad...

the November retail revision will add about .2 to that...means the goods part of PCE was growing at near a 12% annual rate...revise 4th quarter GDP forecasts upwards..

rjs