After the Great Recession had officially began (but prior to the stock market crash of 2008/09) George W. Bush responded to the early signs of economic trouble with a "helicopter drop" in the form of lump sum tax rebates to wage earners to help stimulate the economy. They were provided for in the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008, with support from both the Democrats and the Republicans. The bill was signed into law on February 13, 2008. Most taxpayers received a rebate between $300 to $600 per person (based on adjusted gross incomes from 2007) — and eligible taxpayers also received an additional $300 per dependent child. The rebates were phased out for taxpayers with AGIs greater than $75,000. The total cost of this bill was projected to be $152 billion — just peanuts compared to quantitative easing.

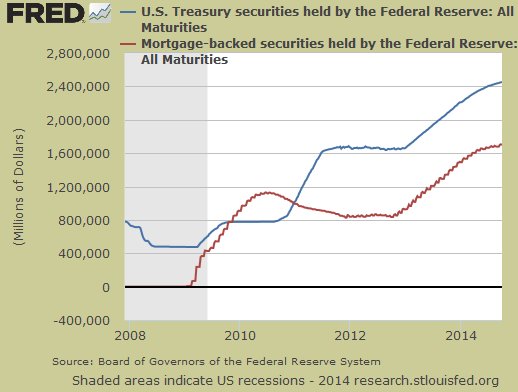

The U.S. Federal Reserve used quantitative easing (QE) as another unconventional monetary policy to stimulate the economy. Before the onset of the Great Recession in 2007, the Fed only held a fraction of what it does today in Treasury notes (almost $800 billion). But beginning in November 2008, they started buying up billions in mortgage-backed securities. The Fed bought billions in these securities and Treasury notes every month in what is known as QE1, QE2 and QE3. (Because of its open-ended nature, QE3 had earned the nickname of "QE Infinity".) Currently the Fed holds a total of $2.7 trillion in federal debt (about what JPMorgan has in total assets).

U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed securities held by the Federal Reserve from Dec. 2007 to the Present

In June 2013, then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke announced a "tapering" of some of the Fed's QE policies (contingent upon positive economic data). He suggested that if inflation followed a 2% target rate and unemployment decreased to 6.5%, the Fed would most likely start raising interest rates. In September 2013, the Fed decided to hold off on scaling back its bond-buying program. This policy is currently being debated, especially now, since the Bureau of Labor Statistics currently reports the "official" unemployment rate as 5.9% and says: "Over the last 12 months, the all items index increased 1.7 percent before seasonal adjustment." (September 2014 CPI data are scheduled to be released on October 22, 2014.) Also, Dean Baker has an interesting post about this (NAIRU) at the Center for Economic Policy and Research.

But before we talk about the tapering of quantitative easing (or expanding it with "QE4"), we really should be discussing another viable alternative: "helicopter drops".

Lately there's been an interesting and ongoing debate, where some have been arguing: rather than using quantitative easing to stimulate the economy, instead, why not use direct cash transfers (like George W. Bush's tax rebates) and give money directly to "people" rather than to banks to boost demand and create more spending — regenerating more growth in the economy.

A particular article from the Counsel on Foreign Affairs has recently received a lot of attention: "Print Less but Transfer More: Why Central Banks Should Give Money Directly to the People" (excerpted and edited):

In a story with clear parallels for today, after Japan’s asset bubble burst [during the Lost Decade], its markets went into a deep dive. Government debt ballooned, and annual growth slowed to less than one percent. In 1998, when their economy was shrinking, Ben Bernanke argued that the Bank of Japan needed to act more aggressively and suggested it consider an unconventional approach: give Japanese households cash directly. Consumers could use the new windfalls to spend their way out of the recession, driving up demand and raising prices. (Japan never used that advice, and is still trying to recover.)

VOX recently published an article referencing that article "To fix the economy, let's print money and mail it to everyone":

For the past six years, the Federal Reserve has been trying very hard to get Americans to spend more. First, it cut interest rates so borrowing was easier. When rates got as low as they could go, it tried to pump money into the economy by buying up tons of bonds from people. So far they've bought trillions worth of US Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities. And while there's evidence this has all helped the economy grow, the course the Fed chose clearly hasn't been sufficient for a rapid, sustained recovery ... The problem is that people aren't spending enough. So why not just have the Fed give people money to spend?

The idea — known as helicopter drops — has a long history in economics ... John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman both endorsed versions of it, but it's most closely associated with former Fed chair Ben Bernanke, who first raised the proposal in the context of Japan's economic malaise in 1999 and repeated it in 2002 as a Fed board member. And the logic behind it is fairly easy even for laymen to understand.

We often talk about what the Fed does to spur the economy as "printing money," but we rarely spell out exactly what that entails. Usually, it means buying up bonds with money the Fed invents on the spot. That increases the money supply, lowers interest rates, and stimulates borrowing ... and used by the Fed to keep interest rates at a certain target. But since the recession, the amounts involved have grown enormously, a policy known as quantitative easing (QE). The Fed has, through three rounds of QE, bought trillions of dollars worth of bonds from financial institutions.

Blyth and Lonergan [at the Counsel on Foreign Affairs] argue the pathways by which QE can be effective are too circuitous. "Low interest rates are simply not stimulating spending, which is what the central bank is trying to achieve," Lonergan says. "Our view is that it'd be much simpler to transfer cash directly. It's simple, it can be quite immediate, and virtually all economists would agree that it would have a material impact on spending."

They argue that the Fed should take the money being used to buy bonds and use it instead to finance checks sent to every household. They'd either make grants of identical size to everybody, or, preferably, larger ones for people in the bottom 80 percent of the income distribution. "Targeting those who earn the least would have two primary benefits," they write. "For one thing, lower-income households are more prone to consume, so they would provide a greater boost to spending. For another, the policy would offset rising income inequality." The plan, they argue, would require much less money than quantitative easing does to be effective: "Print Less but Transfer More," as their Foreign Affairs headline has it. (Continue reading the full VOX article here and a case against "helicopter drops".)

As VOX noted in their article, the idea of "helicopter drops" isn't inherently a left-wing or right-wing idea, and the ideological diversity of their supporters is one of its most intriguing aspects of this proposal. Recently from the National Review, also referencing that same article by the Counsel on Foreign Affairs:

Those who are drawn to Blyth and Lonergan’s approach on egalitarian grounds might object to such a universal transfer, but they shouldn’t, as it is an alternative to the far more inegalitarian quantitative easing approach, the main effect of which is to prop up asset prices ... The chief benefit of helicopter drops is that instead of propping up asset prices (and bailing out big banks and business enterprises) ... they mitigate the consequences of macroeconomic volatility upon the people. While quantitative easing and bailouts disproportionately benefit the asset-owning rich, helicopter drops leave the household income distribution untouched, leaving the question of redistribution to lawmakers. And Blyth and Lonergan appeal to legitimate concerns about the scale of asset purchases by noting that the cash transfers they envision would be modest in comparison:

There is no need, then, for central banks to abandon their traditional focus on keeping demand high and inflation on target. Cash transfers stand a better chance of achieving those goals than do interest-rate shifts and quantitative easing, and at a much lower cost. Because they are more efficient, helicopter drops would require the banks to print much less money. By depositing the funds directly into millions of individual accounts — spurring spending immediately — central bankers wouldn’t need to print quantities of money equivalent to 20 percent of GDP.

The argument for bank bailouts is that they are necessary to prevent a catastrophic deflationary collapse. Yet direct transfers to individuals can do that just as well, if not better. And so banks can be allowed to fail, clearing the ground for new banks to emerge in their place. If Blyth and Lonergan are seeking to build a broad coalition for their proposals, and I think they are, pressing the case against bank bailouts would be a good place to start.

From Aljazeera, "Real Money Matters":

Since November 2008, the Fed has pumped roughly $3 trillion into the economy, and two-thirds of it is sitting in the Federal System earning interest for big banks. The majority of the funds created by QE are gathering dust in the Federal Reserve System as excess reserves over and above what commercial banks are required to hold to protect against loan defaults. Excess Reserves of Depository Institutions have exploded from $267 billion in October 2008 to $2.2 trillion in September 2013. Banks aren’t willing to lend the money out or because there simply isn’t the demand for the loans that could be created. Either way, the banks don’t have to lend excess reserves to realize a return because the Federal Reserve pays 0.25% interest on them.

From the Wall Street Journal (Andrew Huszar): "Confessions of a Quantitative Easer":

I can only say: I'm sorry, America. As a former Federal Reserve official, I was responsible for executing the centerpiece program of the Fed's first plunge into the bond-buying experiment known as quantitative easing. The central bank continues to spin QE as a tool for helping Main Street. But I've come to recognize the program for what it really is: the greatest backdoor Wall Street bailout of all time.

Some people have wondered why ordinary people can't go to the Fed window and get the same low interest rates as the commercial banks. And there are those who believe this cash transfer to "people" instead of commercial banks might be a guise to Socialism; but consider this paraphrase of an old quote: "Under capitalism, man exploits man. Under socialism, it is the other way around." In a sense, the U.S. already uses a form of Socialism. It's called "crony capitalism".

Some people believe that our modern world began when Queen Elizabeth I granted a company of 218 merchants a monopoly of trade to the east of the Cape of Good Hope (near the southern tip of Africa). From the Economist: The Company that Ruled the Waves: "The East India Company foreshadowed the modern world in all sorts of striking ways. It was one of the first companies to offer limited liability to its shareholders. It laid the foundations of the British empire. It spawned the 'Company Man'. And it was the first state-backed company to make its mark on the world [with crony capitalism]. "

From Stumbling and Mumbling (excerpted and edited) "Free Markets need Socialism":

Of course, there's nothing new about state support for business: remember the East India Company? But it could be that there is especial need for it now. In a time of slower technical progress and a dearth of monetizable investment opportunities, capitalism cannot generate sufficient profits under its own steam. Instead, it needs the state to create them by outsourcing, privatizations, bailouts and tax credits wage subsidies. What's more, there are huge pressures on politicians to give business what it wants ... This poses a question. Given these structural tendencies for capitalism to degenerate into cronyism [e.g. crony capitalism], could it be that some form of market socialism would do better? [e.g. competitive socialism. See: Markets not Capitalism] Could it be that, if you are serious about wanting a genuinely free market economy, then you must advocate not capitalism but socialism?

In a genuinely free market economy, capitalism does require some Socialism. The following two articles might better explain why: "Capitalism Requires Government" and "Free Markets are Fraudulent Markets".

Excerpted from "Cash Transfers vs. Quantitative Easing" (also referencing the article by the Counsel on Foreign Affairs):

Rather than having the Federal Reserve create billions/trillions of dollars of new digital dollars out of thin air and "loaning" this new supply of money (M-1) to the commercial banks (who might only reinvest in U.S. Treasury bills and pay themselves huge bonuses), let's take all that new money and create debit cards for $10,000 each* and mail them to every single working-age American citizen with a Social Security number to spend as they wish within the U.S. to create more consumer demand — which in turn will require more supply, which in turn will create more jobs. After the labor pool has absorbed the bulk of the unemployed, we can increase immigration to fill any open jobs — and create yet more demand.

When Paul Krugman recently defined "secular stagnation" as an underlying change in the economy (such as slow growth in the working-age population) he said that it's not the same thing as a slow growing of economic potential, although that might also contribute to secular stagnation (by reducing investment demand as opposed to consumer demand]. He says, "It’s a demand-side, not a supply-side concept".**

* Total cost: Est. $1.6 trillion based on the number currently reported by Social Security as "wage earners" (est. 154 million), and those who are currently reported as "unemployed" (est. 9 million) and those who are "not in the labor force" — but also "want a job" (est. 6 million) — TOTAL: 169 million X $10,000 = $1.6 trillion ... less than the current QE. And that money won't be hoarded ("saved"), but will mostly be spent in consumption. Also, when purchases are made, a portion of state tax would apply, generating more revenues for state budgets as well.

** This post does not address Krugman's opinion on quantitative easing; nor does it address the problem of demand if it's only being supplied by those who offshore jobs; nor does it address the billions spent on mergers and acquisitions, rather than raising domestic wages --- More reading: The Simple Analytics of Helicopter Money: Why It Works – Always.

Comments

The "stimulus"

was so front loaded with special interests, they used foreigners for projects, bought supplies from abroad. Our taxes pouring to other nations and their workers, not ours.

RE: Bought supplies from abroad

"If we purchase a ton of steel rails from England for twenty dollars, then we have the rails and England the money. But if we buy a ton of steel rails from an American for twenty-five dollars, then America has the rails and the money both." -- Abraham Lincoln

Cycles of QE and Stock Sell-offs

In an article at the National Review by Amity Shlaes, the author of The Forgotten Man (about the Great Depression):

Larry Lindsey notes, the cycle of quantitative easing has become predictable: “QE1 ends. Stock market sells off. QE2 begins. Then, QE2 ends. Stock market sells off. Operation Twist starts to be soon followed by a full-blown start of QE3. Now here we are in October and QE3 is finally winding down. This time it was ‘tapered’ rather than abruptly ended. Still, stock market sells off.” Concludes Lindsey: “Whenever the Fed withdraws a stimulus it is going to be painful. Whenever officials flinch and ease because of the pain it just becomes harder next time.”

http://www.nationalreview.com/article/390504/other-bubble-amity-shlaes

A blistering rebuttal can be found here:

http://econospeak.blogspot.com/2014/10/amity-shlaes-and-cliff-asness-are...

A related post by Nick Rowe:

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2014/10/inflatio...

My comment: Suppose, instead of the Fed lending a commercial or shadow bank $1,000 at 0% interest, but instead, just gave $1,000 to an unemployed person without having to repay it back, how many less Treasury notes would be bought by the banks? How many less jobs would be created without QE? How many less bonuses would paid to bank execs?

QE Wall Street

They love their crack cocaine and I heard many claim "maybe the Fed will not withdraw QE now" commentary on the stock downturn days.

Impact of Private Debt?

There's always this talk about govt debt. What about private debt and its impact on the recovery?

The Bush tax rebate provided me with enough 'cash' to make 1 monthly credit card payment. The adjustment in payroll taxes provided for in the first year of Obama's administration amounted to even less. My food costs are very high and my medical expenses have risen -- and this is INDEPENDENT of Obamacare, so don't waste my time pitching your political hype. My salary has remained practically unchanged.

This is true for nearly everyone I speak to.

We as individuals and businesses have buried ourselves with personal and corporate PRIVATE debt. I cannot get out from under it without making some significant changes -- and I assume this is true for the rest of the nation, and I think this is also a global phenomenon. We spent 30 years building up our debts, borrowing like mad men and women. Now we, and a future generation, have to pay it all off. This will take what, three decades?

I remember a bumper sticker in the 1980s -- old folks driving cars with a bumper sticker that read "I am spending my children's inheritance." And it was true. My parents generation spent like crazy, and my generation spent like crazy -- but what WE spent was all borrowed money!

The way economies behave, it is clear that economic booms are fueled by massive increases in loans, and that when private debt grows out of control, that's when the stuff hits the fan. Remember, I can't print more money to cover my debts. Banks have been given a free ride, by shifting their debt burdens to their governments, who are printing money to take up the slack. But the rest of us -- individuals, families and private businesses of all sizes -- have to spend less and use what resources we have to pay off old debts.

To me the issue isn't ONLY that the Fed assumed all these bankers' debts and is printing money to 'paper over' the problem. It isn't an issue in that this has been going on for years now, and the world has not come to an end yet.

To me the greater issue is that the rest of us are haunted by our collective borrowing-and-spending binge and have to keep paying down our old obligations.