Our nation's politicians like to lecture us about free markets whenever we lose our jobs. So maybe the news from yesterday surprised you a little.

The Financial Accounting Standards Board, under pressure from lawmakers, will reconsider its timeline for a controversial rule change that may force banks to bring trillions of dollars in off-balance sheet assets onto their books at its Wednesday meeting.

The rule changes would have put about $5 Trillion of off-balance sheet assets, mostly consisting of mortgage-backed securities, onto the books of the nation's financial institutions. It now appears that the start date for these new accounting rules won't go into effect until after November 15.

After years of efforts by regulators to force financial institutions to open their books to investors, why the sudden change of heart?

To understand that you have to understand what a derivative is, what a Level 3 asset is, and what the National Australia Bank did just a few days ago.

"[Derivatives are] financial weapons of mass destruction and pose a mega-catastrophic risk for the economy."

- Warren Buffett, multi-billionaire investor

First of all, let's address the notable action that the NAB took over the weekend.

NAB’s exposure to the US property market through the CDOs held in its conduits is relatively small – $1.2 billion worth of structured finance assets. The money is in 10 collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) in two conduits (off balance sheet vehicles to which NAB provides “liquidity”).Leaving aside the dodgy nature of the vehicles, the assets themselves were all rated AAA, which technically means a one in 10,000 chance of default.

Stewart, Chaney and the NAB risk committee have now assessed the prospect of loss at 90 per cent, that is a 9,000 in 10,000 chance of default. In other words, the securities have turned out to be far worse than junk.

To repeat: NAB is now expecting 100 per cent loss on $900 million worth of AAA rated debt securities.

So what? So the aussies lost some money on American real estate like everyone else. What has this got to do with me? To answer that, let's look at what happened at Merrill Lynch just yesterday.

Merrill said it will sell a large portion of asset-backed securities and terminate hedges linked to bond insurers; those are two of its most troubled areas since the credit turmoil began last year. It reported earlier this month its fourth straight quarterly loss and write-downs from failed investments approaching $40 billion.Lone Star Funds, a Dallas-based distressed-debt investors based run by John Grayken, will acquire asset-backed securities with a nominal value of $30.6 billion for $6.7 billion. The sale will help cut Merrill's exposure by $11.1 billion from its level on June 27, leaving $8.8 billion of these securities on its books.

For those of you who aren't very quick with math, Merrill is selling those securities for 22 cents on the dollar. Not quite as bad as the 100% write-off by NAB, but close enough. What the article didn't mention was that Merrill was also loaning Lone Star Funds 75% of the cash needed to "buy" these assets off of them.

So then you might ask, what does Merrill have to do with NAB? It turns out, everything.

The National Australia Bank's shock write-down of $830 million worth of collaterallised debt obligations (CDOs) can now be explained.It was triggered by a move from struggling US investment bank Merrill Lynch to get rid of billions worth of CDOs in which the NAB was a co-investor.

Merrill's took a decision to sell the CDOs at a written-down value and the NAB had no option but to follow suit. Its larger write-down than Merrill Lynch (90% vs. 78%) reflects its lower ranking of security.

Welcome to counter-party risk, American-style.

Most of these mortgage-backed securities current live off-balance sheet, where they don't show up on a bank's quarterly report. The bank gets to play make-believe and keep giving huge bonuses to its executives, while telling its shareholders that its portfolio is still strong and solvent.

All the while these supposedly AAA-rated securities decay. At least until after the November election, that is.

Entering Level Three

Banks group their assets into three different levels of accounting.

1) Level 1: Mark-to-Market. These assets are liquid (like Treasuries) and their market values can be easily checked.

2) Level 2: Mark-to-Model.

"Assets that have quoted market prices for similar instruments in active markets, quoted prices for identical or similar instruments in markets that are not active, and model derived valuations in which all significant inputs and significant value drivers in active markets."

There are about $4 Trillion in Level II assets on bank balance sheets.

3) Level 3: Mark-to-Make-Believe.

Level Three assets are the least liquid of the firms' trading assets and therefore are valued using what are called "unobservable inputs."

Level Three assets include real estate, mortgage-backed securities, private equity investments and possibly even "undertakings of great advantage, but nobody to know what they are" (cf. South Sea Bubble).

The three magic words that make an asset a Level 3 asset are "no observable inputs." What this means is that not only are they hard to price, but nearly impossible to sell.

Level 3 assets aren't some tiny problem.

For instance, Bear Stearns had 314% more Level 3 assets than capital before it went bust. Merrill Lynch had 225% more Level 3 assets than capital before this latest fire sale. Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Lehman Brothers, Citigroup, and Fannie Mae all have much more non-liquid assets sitting in Level 3 than they have capital.

Speaking of Merrill Lynch, they are largely unable to raise new capital because of limitation on equity issues when they accepted capital from Temasek (the Singapore sovereign wealth fund) earlier this year. Thus they were forced into doing this fire sale of illiquid assets.

The one thing that the banks don't want to do is to have to find out the real price of these assets at market value. Once they know the value they have to acknowledge the losses.

Citigroup is also in a similar situation when it comes to raising capital.

It's this sort of worthless cr*p that the new regulations will effect. It's this sort of toxic waste that the banks want to keep off their books, and the Federal Reserve is doing everything it can to help in this regard.

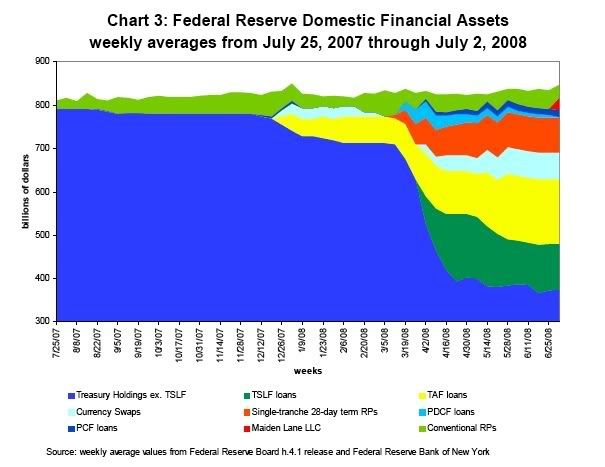

The Fed has gutted its own portfolio by trading Treasuries for mortgage-backed securities and other illiquid assets from investment banks.

The Fed has qualified this by saying that it would only accept AAA-rated securities in exchange. This claim seems laughable when you consider that NAB just wrote off 100% losses on so-called AAA-rated securities.

More importantly, the Fed can't keep this up. According to their last report, their holdings of Treasury securities and "bills were nearly exhausted".

To understand the sheer magnitude of the problem, we must look at what a derivative is.

Weapons of Financial Mass Destruction

Derivative: a) measurement of how a function changes when the values of its inputs change, b) financial instruments whose value is derived from the value of something else.

" Derivatives generate reported earnings that are often wildly overstated and based on estimates whose inaccuracy may not be exposed for many years."

- Warren Buffett

I generally try to stay away from the speculative, doom-and-gloom topics because they tend to get associated with the tinfoil hat crowd. But when that topic shows up in the New York Times, it is no longer in the realm of tinfoil hats.

Credit default swaps form a large but obscure market that will be put to its first big test as a looming economic downturn strains companies’ finances. Like a homeowner’s policy that insures against a flood or fire, these instruments are intended to cover losses to banks and bondholders when companies fail to pay their debts.

To put it simply, a credit default swap (CDS) is a bet between two parties on whether or not a borrower will default on its bonds. The insurer collects premiums from the other party and only has to pay in the case of a default. The swap itself can be sold by either party to a third party.

So far so good? Not so fast.

But during the credit market upheaval in August, 14 percent of trades in these contracts were unconfirmed, meaning one of the parties in the resale transaction was unidentified in trade documents and remained unknown 30 days later. In December, that number stood at 13 percent. Because these trades are unregulated, there is no requirement that all parties to a contract be told when it is sold.As investors who have purchased such swaps try to cash them in, they may have trouble tracking down who is supposed to pay their claims.

To put it another way, the market is almost completely opaque and unregulated.

No one necessarily knows about such investments because they exist off the books, and don't show up in the report or balance sheets of either party. This causes all sorts of problems. For instance, does the holder of the swap actually have the capital to cover a default? An even bigger problem is what happens when a deep recession hits and defaults skyrocket? By spreading the risk around with CDS no safe place remains.

If this sounds suspiciously like Enron, it's because derivatives were the main product that Enron dealt with.

There are other issues as well.

"PAI" (publicly available information) must generally be used to trigger the CDS contract. Recent credit events have been straightforward Chapter 11 filings and bankruptcy. For other credit events (failure to pay or restructuring), there may

be problems in establishing that the credit event took place.This has a systemic dimension. A CDS protection buyer may have to put the reference entity into bankruptcy or Chapter 11 in order to be able to settle the contract. A study by academics Henry Hu and Bernard Black (from the University of Texas) concludes that CDS contracts may create incentives for creditors to push troubled companies into bankruptcy. This may exacerbate losses in case of defaults.

No one has any idea just how sound the market for these derivatives are is open to speculation. That isn't a big deal until you realize that 15 years ago there were no CDS, and now the CDS market is 4 times the size of America's GDP. So how could the government fix a market that is 4 times the size of the GDP if that market freezes up? It's impossible.

The global market for all derivatives is about $500 Trillion. The total global GDP is about $60 Trillion.

Who are the players?

What brought this obscure financial instrument to the attention of the media was troubles at American International Group Inc. (AIG), the world's largest insurer.

It seems their estimated losses had jumped from a $1.2 Billion to $4.88 Billion. The reason for the losses was their exposure to credit default swaps.

AIG's auditors found ``material weakness'' in its accounting for the contracts, and the firm doesn't know what they were worth at the end of 2007, the filing said.

The fact is that even AIG can't tell how much they lost, why they lost it, and how much their remaining CDS are worth.

Not once in its seven-paragraph narrative discussion did AIG say how or why the gross losses on these derivatives had soared after Sept. 30. Rather, in almost-unintelligible jargon, it told how in November it developed a new ability to value some large offsetting gains -- and how it then decided this month to exclude most of them because the data weren't reliable.

And that $4.88 Billion was only through November 30. Considering the credit market troubles of December and January, that number is likely to rise a great deal.

To put this into perspective, AIG only holds about $500 Billion of CDS.

The largest holder of CDS is JP Morgan Chase with $7.8 Trillion. Citibank holds $3 Trillion, and Bank of America another $1.6 Trillion of CDS.

While JPM, Citi, and BofA have been taking body blows from the current troubles in the credit markets, they have yet to acknowledge any significant losses from their CDS holdings. Doesn't that seem rather unlikely given the troubles at AIG?

It seems a lot more likely that the opacity of the CDS market is allowing these major banks to hide their losses. It's even possible that the banks don't even know how much they have lost.

Which brings us back to the NAB and the implications of their actions.

We are now way beyond sub-prime. NAB says that it is suffering a 55 per cent loss on American housing loans – an event that has never happened in the history of a developed country in recent memory. This is an unprecedented event and means that the cost of bailing out the US financial system is now far beyond the highest estimates. A US recession is now locked in, but more alarmingly, 55 per cent loan losses point to the possibility of a depression.It means the cost of bailing out housing exposures to the two mortgage insurers will be so great that it will leave no room to bail out anything else and there are several US banks that are now in big trouble.

"Big trouble" is one way of putting it. "Insolvent" is another, more accurate way.

Comments

Two words

Oh shit.

This looks very, very, very bad. But maybe things have to got worse before they get better.

Polanyi and the Double movement spring to mind. How far can the market go to destroying the basic things that any society needs to survive before it generates a backlash against it?

derivatives

I wrote up a post a while ago on derivatives. I wrote it to explain what the hell is going on for myself. It has some video tutorials in it here.

Actually I do like this diary

Per your comment to my last one.

Wall Street investment banks (ex-Goldman and maybe also JP Morgan) are in deep doo doo. The entire Bush-boom was based on pretend-bucks showing up as credit that were never going to be paid back. Now it's time to pay the piper.

Where I've been calling BS is when people say the FDIC is insolvent. That case is "unproven" at least to use the Scottish term. More later.

That pesky November date

So basically, I should be going long Puts on financials or the XLF with an expiry past November?

Make that February

From today's news.

If they were smart

The banks would be quickly moving to separate those marked losses away from the main commercial banking. But they're not. Something tells me, when this bomb goes off, that ultimately the government will do this. The losses have to be unwind some how for these concerns to continue.

naked shorts

Here's something ridiculous. The SEC put on notice naked shorts on 19 companies, pretty much all of them financials. Now they extended that until August 12. But the thing is, naked shorts are supposed to be illegal. (this means someone can short more stock than has been issued!)

So, are we being set up for the wild short ride?

Naked shorts, bear raids, and short squeezes

As I understand it, there used to be a limited exception to the ban on "naked shorts", and that was for broker/dealers who nevertheless had to use their "best efforts" to locate stock to borrow, first, before they went nekkid. At some point whether formally or just (surprise, surprise) lack of enforcement, the "best efforts" requirement ceased to exist. This enabled "bear raids" where people could simulataneously by enormous amounts of short interest and at the same time pass on rumors of, e.g., insolvency.

It's not clear to me at all that this wasn't the case with Fannie and Freddie.

The fact remains, if naked shorting is bad, then presumably it is bad for all publicly traded stocks, not just certain favored "crony" stocks.

In a similar vein, BTW, I'm wondering about the June 8 Morgan Stanley note calling for $150/barrel oil by July 4, that it appears just happened to come out simultaneously with SemGroup being caught short in oil. Their forced unwinding may have been behind the recent upward spike, and of course it put them out of business. Did somebody know something and apply a short squeeze?

I agree with you

That's what I'm seeing, zero enforcement, a law which is supposed to apply to all stocks, yet magically was "whipped out" for just 19 and on a "timed" basis, and yes, isn't it interesting some of these announcements of commodities going on? Another example is the rumor mill on WaMu and the piling on of shorts.

There are rules, and then there are "rules"

I covered naked short selling in this diary.

First of all, naked short selling is supposed to be illegal. It's common sense. Should it be illegal to sell something that you don't own? Yes.

Secondly, why only these 19 banks? Why not other banks that are in real trouble, like WaMu?

Thirdly, large banks are usually not the targets of naked shorts. Small businesses are, and these can be wiped out by naked shorts.

Finally, why only a notice? Probably because the people most responsible for the naked shorts are also the ones that the SEC is now shielding.

Well, let's put on our tinfoil hats

Suppose you were a crony corporatist President, Fed Chairman, or Treasury Secretary. Your cronies, the Wall Street investment banks, come to you doing their best imitation of Jim Cramer's "They're dying out there!!!" meltdown from last August.

Your cronies are insolvent.

How do you save them? Maybe you (1) lower interest rates so they can rebuild their balance sheets, (2) look the other way while they run up commodities and profit mightily from same, (3) allow them to move their toxic garbage onto Federal agency balance sheets, (4) look the other way while they profit mightily from mounting bear raids on other stocks, and then (5) immunize them against retaliatory bear raids.

Just supposin'....

NY Times catches the idea

Looks like the NYT is also asking questions about the value of banks assets because of the Merrill Lynch deal.

WOW! What a potential bargain

For the moral investor. Take an asset-backed loan off of the bank at $.22 on the dollar- and offer the family to change their unaffordable mortgage into rent overnight without needing to move.

Suddenly you've just created your own retirement business. At 1/5th the price.

-------------------------------------

Maximum jobs, not maximum profits.

It's even better than that

According the NY Times article, Merrill is loaning Lone Star $5 Billion to buy the $6.7 Billion in assets off of them.

Now here's the kicker: if the value of the mortgage-backed securities deteriorates even further then Lone Star has to eat the first $1.7 Billion in losses. However, for every dollar the value of the assets fall past the first $1.7 Billion Merrill Lynch is on the hook.

So in other words, if the value of the assets fall to zero, then Lone Star would lose $1.7 Billion, but Merrill Lynch would lose another $5 Billion.